People have been dyeing fibre, yarn and cloth for millennia and dyed fabrics that are more than four thousand years old have been found in Egyptian tombs as well as hieroglyphs that describe the extraction and use of natural dyes. A Greek papyrus (Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis) dated to around the third century AD has survived that has around seventy recipes dealing with the mordanting and dyeing of cloth. A ninth century manuscript in the Benedictine monetary of Reichenau called Mappae Clavicula contained twenty dye recipes with instructions for dyeing fabric and leather. Quite a number of sixteenth and seventeenth century books dealing with dyes and dying survive as well as eighteenth and nineteenth century manuals that all show how little the trade changed over the centuries.

People have been dyeing fibre, yarn and cloth for millennia and dyed fabrics that are more than four thousand years old have been found in Egyptian tombs as well as hieroglyphs that describe the extraction and use of natural dyes. A Greek papyrus (Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis) dated to around the third century AD has survived that has around seventy recipes dealing with the mordanting and dyeing of cloth. A ninth century manuscript in the Benedictine monetary of Reichenau called Mappae Clavicula contained twenty dye recipes with instructions for dyeing fabric and leather. Quite a number of sixteenth and seventeenth century books dealing with dyes and dying survive as well as eighteenth and nineteenth century manuals that all show how little the trade changed over the centuries.

Until the 1850s virtually all dyes were derived from natural sources, mostly from plants and a few from insects and shellfish. The most common dye stuffs such as madder, weld, woad and indigo where well known very early on and remained in used until William Henry Perkin accidentally discovered the first synthetic organic dye in 1856. With the development of aniline dyes the use of natural dyes declined rapidly.

People have been dyeing fibre, yarn and cloth for millennia and dyed fabrics that are more than four thousand years old have been found in Egyptian tombs as well as hieroglyphs that describe the extraction and use of natural dyes. A Greek papyrus (Papyrus Graecus Holmiensis) dated to around the third century AD has survived that has around seventy recipes dealing with the mordanting and dyeing of cloth. A neneth century manuscript in the Benedictine monetary of Reichenau called Mappae Clavicula contained twenty dye recipes with instructions for dyeing fabric and leather. Quite a number of sixteenth and seventeenth century books dealing with dyes and dying survive as well as eighteenth and nineteenth century manuals that all show how little the trade changed over the centuries.

Until the 1850s virtually all dyes were derived from natural sources, mostly from plants and a few from insects and shellfish. The most common dye stuffs such as madder, weld, woad and indigo where well known very early on and remained in used until William Henry Perkin accidentally discovered the first synthetic organic dye in 1856. With the development of aniline dyes the use of natural dyes declined rapidly.

Madder roots produce a strong red dye and is used to produce reds, oranges and pinks with an alum mordant. An iron mordant will produce browns, greys and even purples.

Madder roots produce a strong red dye and is used to produce reds, oranges and pinks with an alum mordant. An iron mordant will produce browns, greys and even purples.

Madder is native to western and central Asia and has become naturalized in many areas of central and southern Europe. Madder has been used for centuries and cotton textiles dyed with it, dated around three thousand BC, are known from the Indus civilization. It has been found on linen in the Nile Valley tombs and was prized by the ancient Greeks and Romans. In the Middle Ages madder became of great importance in Europe and was grown extensively in France and Germany. From the tenth century it was grown in Holland and by the sixteenth century the Dutch became the biggest producers in the world. Madder was the principle red dye in the medieval period and continued to be used throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Madder roots produce a strong red dye and is used to produce reds, oranges and pinks with an alum mordant. An iron mordant will produce browns, greys and even purples.

Madder is native to western and central Asia and has become naturalized in many areas of central and southern Europe. Madder has been used for centuries and cotton textiles dyed with it, dated around three thousand BC, are known from the Indus civilization. It has been found on linen in the Nile Valley tombs and was prized by the ancient Greeks and Romans. In the Middle Ages madder became of great importance in Europe and was grown extensively in France and Germany. From the tenth century it was grown in Holland and by the sixteenth century the Dutch became the biggest producers in the world. Madder was the principle red dye in the medieval period and continued to be used throughout the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Buckthorn berries, also known as Persian berries and Avignon berries, produce a strong yellow dye and is used to produce yellows with an alum mordant and greens with an iron mordant.

Buckthorn berries, also known as Persian berries and Avignon berries, produce a strong yellow dye and is used to produce yellows with an alum mordant and greens with an iron mordant.

Buckthorn is native to Europe, northwest Africa and the near east and has been cultivated in Europe since Roman times. Buckthorn berries have long been used as a dye and the earliest written reference to their use that I've come across is a recipe to dye skins green in the mid-15th century Italian manuscript Segreti per Colori or Secrets of Colours. They are used in many of the yellow and green recipes in the 1548 Italian dyers manual "Plictho de Lare de Tentori ...." to dye both cloth and leather and they continued to be used across Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and into the nineteenth century.

Buckthorn berries, also known as Persian berries and Avignon berries, produce a strong yellow dye and is used to produce yellows with an alum mordant and greens with an iron mordant.

Buckthorn is native to Europe, northwest Africa and the near east and has been cultivated in Europe since Roman times. Buckthorn berries have long been used as a dye and the earliest written reference to their use that Ive come across is a recipe to dye skins green in the mid-15th century Italian manuscript Segreti per Colori or Secrets of Colours. They are used in many of the yellow and green recipes in the 1548 Italian dyers manual "Plictho de Lare de Tentori ...." to dye both cloth and leather and they continued to be used across Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and into the nineteenth century.

Walnut hulls are the husks that protect the nuts as they grow. They produce a substantive dye which means they do not require a separate mordant and produce strong browns. With an iron mordant they produce good greys.

Walnut hulls are the husks that protect the nuts as they grow. They produce a substantive dye which means they do not require a separate mordant and produce strong browns. With an iron mordant they produce good greys.

Walnut is native from south-east Europe to south-west China. English walnut has been in Britain since the time of the Romans who are credited with spreading the tree through most of Western Europe and parts of North Africa. Walnut dyes are historically important and Pliny records their use as a hair dye in the first century AD. The German Innsbruck Manuscript from 1330 has a recipe for a black dye using walnut hulls as does A Profitable Booke of Mr. Iohn Perkins 1588. The eighteenth century dyers manual 'The Dyer's Assistant' 1778 says of walnut hulls 'Of all the ingredients used for the brown dye, the walnut rind is the best; its shades are finer, its colour is lasting, it softens the wool, renders it of a better quality, and easier to work'. They continue to be used into the 19th century with recipes using it in The Country Dyer's Assistant by Asa Ellis 1798 and The Household Cyclopaedia: Dying, in all its Varieties 1880. Walnut hulls are still used today to make Van Dyke crystals which are used to make ink, paints and wood stain.

Walnut hulls are the husks that protect the nuts as they grow. They produce a substantive dye which means they do not require a separate mordant and produce strong browns. With an iron mordant they produce good greys.

Walnut is native from south-east Europe to south-west China. English walnut has been in Britain since the time of the Romans who are credited with spreading the tree through most of Western Europe and parts of North Africa. Walnut dyes are historically important and Pliny records their use as a hair dye in the first century AD. The German Innsbruck Manuscript from 1330 has a recipe for a black dye using walnut hulls as does A Profitable Booke of Mr. Iohn Perkins 1588. The eighteenth century dyers manual 'The Dyer's Assistant' 1778 says of walnut hulls 'Of all the ingredients used for the brown dye, the walnut rind is the best; its shades are finer, its colour is lasting, it softens the wool, renders it of a better quality, and easier to work'. They continue to be used into the 19th century with recipes using it in The Country Dyer's Assistant by Asa Ellis 1798 and The Household Cyclopaedia: Dying, in all its Varieties 1880. Walnut hulls are still used today to make Van Dyke crystalswhich are used to make ink, paints and wood stain.

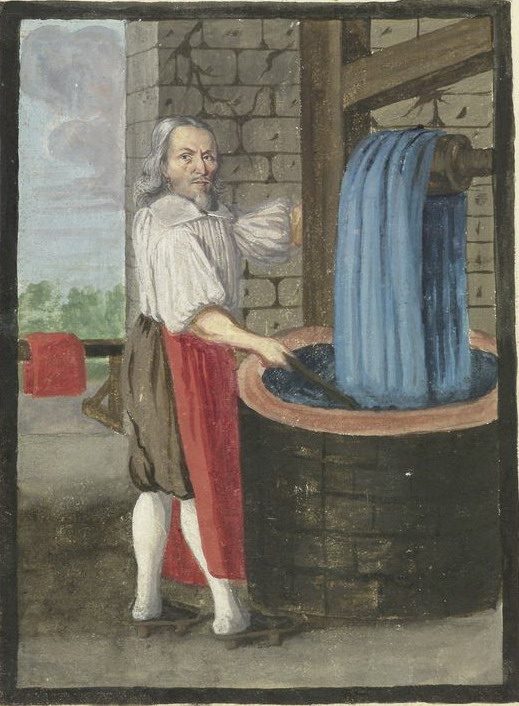

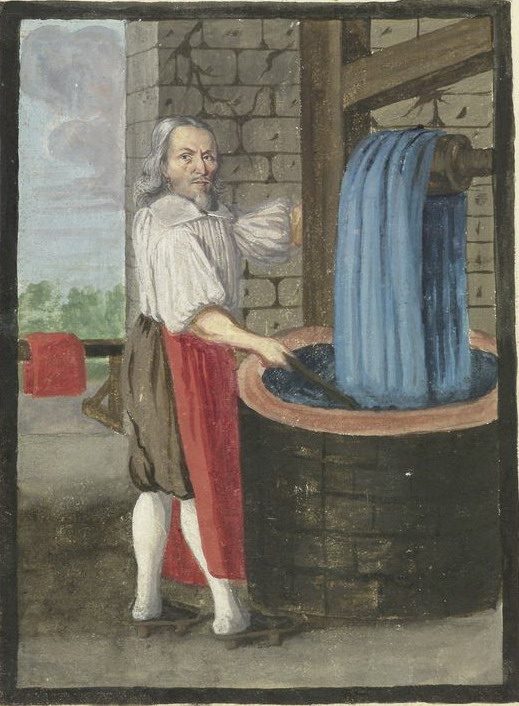

Woad and indigo produce clear blues and when overdyed with yellow dyes produce bright greens. The process of dyeing with woad and indigo is very different to other dyes. Most dyes are extracted by simply heating the dye stuff in water but with woad and indigo the active component of the dye is insoluble in water and requires a fermentation process to extract the dye. The dye components are chemically identical in both woad and indigo and so are the colours they produce.

Woad and indigo produce clear blues and when overdyed with yellow dyes produce bright greens. The process of dyeing with woad and indigo is very different to other dyes. Most dyes are extracted by simply heating the dye stuff in water but with woad and indigo the active component of the dye is insoluble in water and requires a fermentation process to extract the dye. The dye components are chemically identical in both woad and indigo and so are the colours they produce.

Woad is native to Europe, western Asia and North Africa and has been cultivated in Europe for many centuries. Egyptian hieroglyphics from 1500 BC refer to the use of blue dyes and in Roman times Pliny describes how woad was used. By the Middle Ages woad had become very important throughout Europe as the principle blue dye and was widely used into the eighteenth century.

Indigo is a large genus of about seven hundred species which occur mainly in the tropics. The most widely cultivated species, Indigofera tinctoria, probably originated in India. Use of indigo is mentioned in Indian manuscripts from the fourth century BC and it was introduced by the Arabs into the Mediterranean by the eleventh century. By the late fifth century Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to China, allowing indigo to be imported directly into Europe. Indigo was being imported into Britain in the sixteenth century and by the end of the seventeenth century it had virtually replaced woad. Indigo is still used today most commonly to dye denim jeans.

Woad and indigo produce clear blues and when overdyed with yellow dyes produce bright greens. The process of dyeing with woad and indigo is very different to other dyes. Most dyes are extracted by simply heating the dye stuff in water but with woad and indigo the active component of the dye is insoluble in water and requires a fermentation process to extract the dye. The dye components are chemically identical in both woad and indigo and so are the colours they produce.

Woad is native to Europe, western Asia and North Africa and has been cultivated in Europe for many centuries. Egyptian hieroglyphics from 1500 BC refer to the use of blue dyes and in Roman times Pliny describes how woad was used. By the Middle Ages woad had become very important throughout Europe as the principle blue dye and was widely used into the eighteenth century.

Indigo is a large genus of about seven hundred species which occur mainly in the tropics. The most widely cultivated species, Indigofera tinctoria, probably originated in India. Use of indigo is mentioned in Indian manuscripts from the fourth century BC and it was introduced by the Arabs into the Mediterranean by the eleventh century. By the late fifth century Vasco da Gama discovered a sea route to China, allowing indigo to be imported directly into Europe. Indigo was being imported into Britain in the sixteenth century and by the end of the seventeenth century it had virtually replaced woad. Indigo is still in use today and is commonly used to dye denim jeans.

Karl Robinson - Dyer

2 Noble Street

Wem

Shropshire SY4 5DZ

United Kingdom